The Situation of Bahá’ís in Iran

Following the Islamic Revolution of Iran in 1979, members of the Bahá’í Faith—the largest non-Muslim religious minority in the country—have been subjected to a relentless campaign of systematic persecution. The goal of this state-sponsored campaign is to eradicate the Bahá’í community as a viable entity.

Issues and campaigns

Background

In response to growing international and domestic opposition to the persecution of Bahá’ís, the Iranian government has shifted its strategy of oppression, moving away from arrests and imprisonments to more easily obscured measures such as economic and educational exclusion.

As such, its nationwide effort to crush the Bahá’í community in Iran and to destroy it as a cohesive community continues unabated. The government has greatly intensified its campaign of anti-Bahá’í propaganda in the media, apparently in the hope of turning the Iranian public away from any show of support for acceptance of the Bahá’í Faith. And, while attempting to conceal its economic and educational repression with various ruses, it continues to prevent Bahá’ís from earning a living in certain professions or from going to university. It has also supported the legal confiscation of Bahá’í-owned properties.

Canadian Members of Parliament speak out about land confiscations in Iran

Meanwhile, in international forums like the United Nations, the government falsely claims that Bahá’ís have all the rights of citizenship, are free to attend university, and, even, are “wealthy.”

The Phases of Persecution

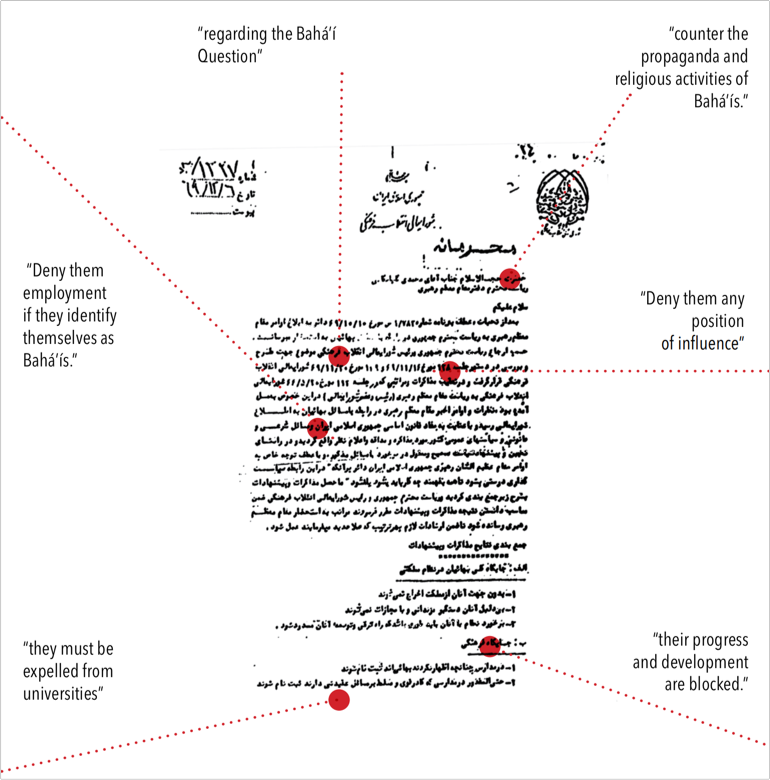

During the first decade of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s existence, more than 200 Bahá’ís — mostly leaders within the community— were killed or executed. Hundreds more were tortured or imprisoned. Formal Bahá’í institutions were banned. Tens of thousands of Bahá’ís lost jobs, access to education, and other rights — all solely because of their religious belief. In the second decade, the government’s anti-Bahá’í strategy shifted its focus to social, economic, and educational discrimination, evidently to mollify international critics. The new emphasis was designed to “block the progress and development” of the Iranian Bahá’í community, according to a secret 1991 memorandum signed by Iran’s Supreme Leader that ominously set policy for dealing with “the Bahá’í Question.” It was quietly implemented, even as the government of President Mohammad Khatami projected an image of moderation around the world.

This 1991 Iranian government memorandum outlines a broad plan to block the development of the Iranian Bahá’í community. It remains the lynchpin of Iran’s strategy of persecution today. The callouts are various phrases from the memorandum, which was signed by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. Archives of Bahá’í Persecution in Iran

In the third decade, especially following the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005, the government stepped up its harassment of Bahá’ís, by using revolving door arrests and increased imprisonment, the identification and monitoring of Bahá’ís, and more raids and harassment at the local level. The government also made clear it would not prosecute those who attacked Bahá’ís, and there was a measurable rise in violent attacks on Bahá’ís and their properties.

Now in its fourth decade, the persecution of Iranian Bahá’ís is marked by a sustained and concealed effort on all fronts — despite the promises of the previous president, Hassan Rouhani, to end religious discrimination. Bahá’ís continue to be regularly arrested, detained, and imprisoned. Young Bahá’ís continue to be denied access to higher education through a variety of deceptive practices. Economic policies targeting small shops and businesses — one of the few remaining sources of income for Bahá’ís and their families—also continue unabated.

Economic and Social Exclusion

Other types of oppression, such as strict limits on the right to assemble and worship and the wholesale dissemination of anti-Bahá’í propaganda in the government-led news media, also continue. Hundreds of attacks on Bahá’ís or Bahá’í-owned properties — including cemeteries — go unprosecuted and unpunished, creating a sense of impunity for attackers.

Destroyed portions of a Bahá’í cemetery in Sanandaj, Iran (2013). BWNS

A top UN human rights expert has said that the government-led persecution spans “all areas of state activity, from family law provisions to schooling, education, and security.” Put another way: the oppression of Iranian Bahá’ís extends from cradle to grave.

Since 2013, hundreds of Bahá’ís have been arrested, there have been hundreds of documented incidents of economic persecution, ranging from threats and intimidation to outright shop closings, and dozens of Bahá’ís have been expelled from university while thousands have been blocked from enrollment. Since 2017, more than 33,000 pieces of anti-Bahá’í propaganda have been disseminated in the Iranian media.

Over the years, numerous documents have emerged that clearly prove such incidents reflect nothing less than official government policy, the aim of which is the systematic destruction of the Iranian Bahá’í community as a viable entity in the country’s national life. These documents, moreover, show it is a policy that emanates from the highest levels of government.

Solidarity and Constructive Resilience

Iranians from all walks of life — clerics, journalists, lawyers, human rights activists, and ordinary citizens — have stood with Bahá’ís in their quest for citizenship rights and religious freedom. Some Iranians have even chosen to work alongside Bahá’ís in their community-building activities.

Moreover, in their response to the persecution, the Bahá’ís of Iran have refused to succumb to the ideology of victimization. Instead, they have found reserves of surprising resilience. Rather than yielding to oppression, Bahá’ís have bravely approached the very same officials who seek to persecute them, using legal reasoning based on Iranian law and the country’s constitution. Despite the daily pressures and hardships they face, not to mention efforts by the government to encourage them to flee their homeland, many Bahá’ís have chosen to stay. They believe firmly that it is their responsibility to contribute to the progress and advancement of their homeland, an ideal put into action through small-scale efforts, such as literacy programs, often undertaken in collaboration with fellow citizens.

A Litmus Test of Reform

Required by their teachings to eschew violence and partisan political involvement, Bahá’ís pose no threat to the government. As such, the government’s policies towards them provide a litmus test of Iran’s genuine commitment to human rights, tolerance, and moderation.

In recent years, Iranian officials have at various times declared that their country is ready to open a new chapter in its relations with the outside world. There are concrete signs to which the international community might look to signify Iran’s willingness to change. These could include President Raisi informing the world that the 1991 Bahá’í Question memorandum has been rescinded — and calling for an end to incitement of hatred against Bahá’ís. Bahá’í students could once again be admitted to study at university. Bahá’í-owned lands that have been expropriated by state authorities could be legally restored to their rightful owners. The ongoing state-sponsored campaign of hate propaganda against Bahá’ís could be brought to a halt. These steps, among others, would mark concrete progress towards the emancipation of Iran’s Bahá’í community.